jQuery is a household name among web developers who have been around the block. Initially released in 2006, it took the web development world by storm with its easy and intuitive syntax for navigating a document, selecting DOM elements, handling events, and making AJAX requests. At its peak in 2015, jQuery featured on 62.7 percent of the top one million websites and 17 percent of all Internet websites.

A decade later, jQuery is not the shiny new kid on the block anymore. Most of the original pain points jQuery solved, such as DOM manipulation and inconsistent browser behavior, are gone thanks to modern browser APIs.

But jQuery is still widely used. According to SimilarWeb, as of August 11, 2025, nearly 195 million websites use it. That means many developers, like me, still use it every day. And like me, you might prefer it in certain cases.

So, in this article, I’ll share when it still makes sense to use jQuery and when not. Don’t worry: I’m not arguing we should replace React with jQuery. And I’m not here to romanticize 2008. In 2025, I simply still find myself reaching for jQuery because it’s the right tool for the job.

A Brief History of jQuery

To determine when it makes sense to use jQuery and when not, it helps to know why it was created in the first place and what problems it aimed to solve.

When John Resig launched jQuery at BarCamp NYC in January 2006, the web was a different place. Features we take for granted today were absent from most browsers:

- No

querySelectorAll: Selecting DOM elements across browsers was messy. In the mid-2000s, none of the available element selectors, likegetElementByIdorgetElementsByClassName, could select elements using complex CSS queries. - Inconsistent event handling:

addEventListenerwasn’t universal. While browsers like Firefox, Safari, and Chrome supported the W3C event model withaddEventListener, Internet Explorer (before IE9) used Microsoft’s proprietary model withattachEvent. These two models differed from each other in almost all functional aspects. - Different browsers had different APIs for

XMLHttpRequest. While browsers like Firefox and Safari offered the familiarXMLHttpRequest, Internet Explorer (before IE7) used ActiveX objects to give JavaScript network capabilities. This meant you had to use a bunch ofif-elseblocks to make an AJAX request. - CSS manipulation quirks: In the 2000s and early 2010s, many CSS features were implemented inconsistently across browsers, which made it difficult to manipulate CSS with JS.

jQuery solved all of this with a simple, chainable syntax and consistent cross-browser behavior. It offered a streamlined, chainable API for DOM traversal, event handling, and AJAX—far simpler than cross-browser native JavaScript at the time. These features made jQuery become the go-to JavaScript library in the 2010s, powering everything from personal blogs to Fortune 500 sites. In 2012, a W3Techs survey found that jQuery was running on 50 percent of all websites, and by 62.7 percent of the top 1M websites used it.

Where jQuery Still Makes Sense

Although jQuery’s glory days are clearly behind us, it still works well in some situations. Here are the scenarios where I still choose jQuery:

Legacy Projects

Even now in 2025, a W3Techs survey shows that jQuery is used in 77.8 percent of the top 10M websites in 2025. This is mostly legacy usage—old apps that use jQuery because switching to a more modern framework is a costly endeavour. This is clear when you look at the version statistics. In a 2023 survey across 500 organizations, only 44 percent use maintained versions (3.6.0 or newer), while 59 percent run older versions (1.x to 3.5.1)

I maintain a few legacy projects like these that were written with jQuery, and I can tell you why they’re still around: they just work. So as the adage goes, “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.”

Many large enterprises, government sites, corporate intranets, and many WordPress plugins and themes still rely on jQuery. Rewriting these sites to pure JavaScript or a modern framework is a time-consuming, expensive endeavour that can also introduce new challenges and bugs. Most of the time, all that effort and risk aren’t worth the relatively small benefits in the short term.

The truth is this: the codebase I inherited, built in the jQuery era, works. The business logic is robust, the profit margins are healthy, and—most surprisingly—shipping new features feels like slipping into a worn leather jacket: unfashionable, but comfortable. - Marc Boisvert-Duprs

Yes, most jQuery plugins are no longer actively maintained or have been deprecated, so depending on them is a security risk. Abandoned plugins may become incompatible or insecure as browsers continue to evolve. So, legacy projects that use jQuery and jQuery plugins should eventually migrate away from jQuery.

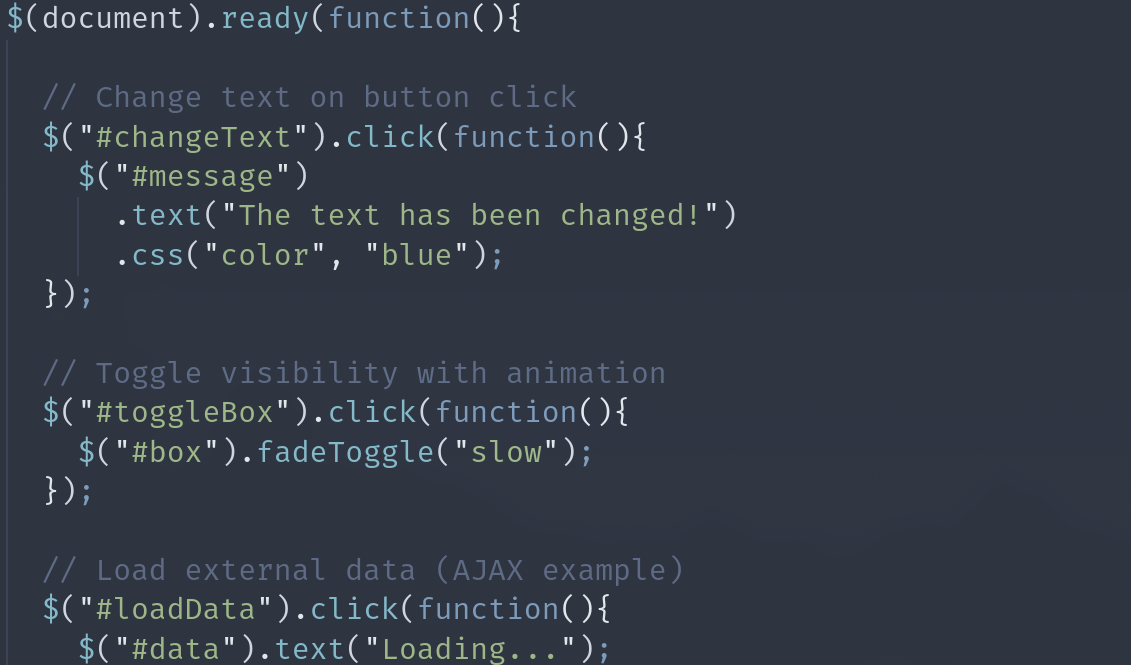

Quick Prototyping without Build Tools

Developers often need to prototype very simple frontend apps, be it for throwaway demos, internal tools, or proof-of-concept pages. Sometimes the spec may even require a very basic frontend with minimal interactivity (for example, a static page with a simple form and a button).

jQuery is a perfect choice for these situations. Simply drop in a <script> tag from a CDN and get animations, DOM manipulation, and AJAX in minutes—no need for npm, bundlers, transpilers, or complicated frameworks with hundreds of dependencies. It’s also great for running quick commands from the DevTools console, especially if you want to experiment with an app.

But why not use a more modern but lightweight framework like Alpine.js? Personally, I’m intimately familiar with jQuery: I’ve used it since the beginning of my web development journey. I love its simplicity and ease of use. The minor improvements a new framework can make in this scenario don’t offset the time spent learning a new tool.

Complex DOM Manipulation in Different Browser Contexts

Hopefully, you don’t have to support older browsers that lack the standard querySelector, or browsers like Internet Explorer, notorious for their non-standard behavior. Unfortunately, some of us still need to maintain apps that run on these browsers.

While native JS is perfectly fine for modern browsers, if you’re building something that has to run on older embedded browsers (think: kiosk software, older enterprise or university intranets, or web apps inside legacy desktop apps), jQuery’s normalization saves you from manual polyfilling, and its CSS selector lets you perform complex DOM manipulations easily.

Simple Animations without CSS Keyframes

As someone who primarily works with backend apps, I don’t often need to code animations for the frontend. But when I do need to create basic chained animations (fading, sliding, sequencing multiple elements, etc.), jQuery’s .animate()is simpler (and more lightweight) to write than juggling CSS animations and JS event callbacks.

Simple AJAX with HTML Server Responses

I was recently tasked to make some upgrades to an ancient app with a PHP backend. Imagine my surprise when I discovered that the server returns HTML fragments, and not JSON APIs. In this case, jQuery’s .load() and .html() methods can be simpler and more efficient than writing fetch() boilerplate with DOM parsing.

For example, I can extract a DOM element from the results of an AJAX request, and load it into an element like so:

// Replace #comments with just the #comments-list from the server response

$('#comments').load('/article/1 #comments-list');

Whereas the same thing in native JS would be:

fetch('/article/1')

.then(res => res.text())

.then(html => {

const doc = new DOMParser().parseFromString(html, 'text/html');

const comments = doc.querySelector('#comments-list');

document.querySelector('#comments').innerHTML = comments.outerHTML;

})

Yes, while the jQuery syntax is more straightforward, both approaches are doing the same thing under the hood, so there’s not a huge performance gain. In the jQuery version, you also have the added overhead of bundling the jQuery library. So, it’s a tradeoff between simplicity and bundle size.

When You Should Not Use jQuery

While jQuery still makes sense in some situations, there are some cases where I would never use jQuery.

Building a Modern, Component-Driven Frontend

If I’m building a modern frontend app with lots of reactivity and reusable components, I’d use a modern framework like React or Vue with native features for DOM manipulation.

Frameworks like React, Vue, Svelte, or Angular handle DOM rendering in a virtualised way. Direct DOM manipulation with jQuery conflicts with their data-binding approach, causing state mismatches and bugs.

For example, in React, calling $('#el').html('...') bypasses React’s virtual DOM and React won’t know about the change. This will inevitably lead to bugs that are difficult to diagnose.

When Simple Vanilla JS Is Enough

Most of jQuery’s once-killer features, such as selectors, AJAX, events, and animations, are now native in JavaScript:

document.querySelectorAll()replaces$().fetch()replaces$.ajax().element.classListreplaces.addClass()/.removeClass().element.animate()handles animations.

If I’m just toggling classes or making a fetch call, adding jQuery is wasteful.

Targeting Modern Browsers Only

jQuery’s major draw between 2008 and 2015 was its cross-browser compatibility, which was necessary due to quirks in IE6–IE9. It simply wasn’t practical to write browser-specific JS for all the different versions of IE. With jQuery, the quirks were abstracted away.

When IE was discontinued, this usefulness is no longer relevant.

So if the app I’m working on needs to support only modern browsers, I don’t need most of jQuery’s compatibility layer.

Projects Already Using Modern Tooling

Mixing jQuery and framework code leads to a “hybrid monster” that’s difficult to maintain.

jQuery can conflict with existing frameworks, which can cause hard-to-fix bugs. If my project is already written in another framework, I avoid including jQuery.

Alternatives to jQuery

Sometimes, I need to use some features of jQuery, but I can’t justify including it in its entirety. Here are some libraries I use in cases like these.

DOM Selection and Traversal

- Native DOM API (most common replacement) using

document.querySelector()anddocument.querySelectorAll() - Cash: jQuery-like API, tiny (~10KB), works with modern browsers

- Zepto.js: lightweight jQuery-compatible library for mobile-first projects

AJAX/HTTP Requests

- Native

fetch()API - Axios: promise-based HTTP client with interceptors and JSON handling.

Event Handling

- Native events using

element.addEventListener() - delegate-it: small utility for jQuery-style event delegation

Animations

- CSS transitions and animations (native, GPU-accelerated)

- Web Animations API

- GSAP: Powerful animation library, much more capable than

.animate()in jQuery.

Utilities

* Lodash: collection iteration, object/array utilities, throttling, debouncing

* Day.js: date manipulation in a tiny package (instead of jQuery’s date plugins)

All-in-One Mini jQuery Replacements

If you still like a single API but want it lighter than jQuery:

- Umbrella JS: ~3KB, jQuery-like API

- Bliss: focuses on modern features, syntactic sugar, and chaining

- Cash: as mentioned above, the closest modern equivalent

jQuery Still Has a Job

In 2025, jQuery isn’t the cutting-edge choice for building complex, highly interactive single-page applications that it was in the 2010s, and that’s perfectly fine. While modern frameworks dominate the headlines, jQuery remains a reliable, well-understood tool that solves the problems it was designed for, simply and effectively.

In the end, the “right” tool is the one that meets your project’s needs, and for countless developers and businesses, jQuery continues to be that.