Trust is the most important consideration when you connect AI assistants to real tools. While MCP containerization provides strong isolation and limits the blast radius of malfunctioning or compromised servers, we’re continuously strengthening trust and security across the Docker MCP solutions to further reduce exposure to malicious code. As the MCP ecosystem scales from hundreds to tens of thousands of servers (and beyond), we need stronger mechanisms to prove what code is running, how it was built, and why it’s trusted.

To strengthen trust across the entire MCP lifecycle, from submission to maintenance to daily use, we’ve introduced three key enhancements:

- Commit Pinning: Every Docker-built MCP server in the Docker MCP Registry (the source of truth for the MCP Catalog) is now tied to a specific Git commit, making each release precisely attributable and verifiable.

- Automated, AI-Audited Updates: A new update workflow keeps submitted MCP servers current, while agentic reviews of incoming changes make vigilance scalable and traceable.

- Publisher Trust Levels: We’ve introduced clearer trust indicators in the MCP Catalog, so developers can easily distinguish between official, verified servers and community-contributed entries.

These updates raise the bar on transparency and security for everyone building with and using MCP at scale with Docker.

Commit pins for local MCP servers

Local MCP servers in the Docker MCP Registry are now tied to a specific Git commit with source.commit. That commit hash is a cryptographic fingerprint for the exact revision of the server code that we build and publish. Without this pinning, a reference like latest or a branch name would build whatever happens to be at that reference right now, making builds non-deterministic and vulnerable to supply chain attacks if an upstream repository is compromised. Even Git tags aren’t really immutable since they can be deleted and recreated to point to another commit. By contrast, commit hashes are cryptographically linked to the content they address, making the outcome of an audit of that commit a persistent result.

To make things easier, we’ve updated our authoring tools (like the handy MCP Registry Wizard) to automatically add this commit pin when creating a new server entry, and we now enforce the presence of a commit pin in our CI pipeline (missing or malformed pins will fail validation). This enforcement is deliberate: it’s impossible to accidentally publish a server without establishing clear provenance for the code being distributed. We also propagate the pin into the MCP server image metadata via the org.opencontainers.image.revision label for traceability.

Here’s an example of what this looks like in the registry:

# servers/aws-cdk-mcp-server/server.yaml

name: aws-cdk-mcp-server

image: mcp/aws-cdk-mcp-server

type: server

meta:

category: devops

tags:

- aws-cdk-mcp-server

- devops

about:

title: AWS CDK

description: AWS Cloud Development Kit (CDK) best practices, infrastructure as code patterns, and security compliance with CDK Nag.

icon: https://avatars.githubusercontent.com/u/3299148?v=4

source:

project: https://github.com/awslabs/mcp

commit: 7bace1f81455088b6690a44e99cabb602259ddf7

directory: src/cdk-mcp-server

And here’s an example of how you can verify the commit pin for a published MCP server image:

$ docker image inspect mcp/aws-core-mcp-server:latest \

--format '{{index .Config.Labels "org.opencontainers.image.revision"}}'

7bace1f81455088b6690a44e99cabb602259ddf7

In fact, if you have the cosign and jq commands available, you can perform additional verifications:

$ COSIGN_REPOSITORY=mcp/signatures cosign verify mcp/aws-cdk-mcp-server --key https://raw.githubusercontent.com/docker/keyring/refs/heads/main/public/mcp/latest.pub | jq -r ' .[].optional["org.opencontainers.image.revision"] '

Verification for index.docker.io/mcp/aws-cdk-mcp-server:latest --

The following checks were performed on each of these signatures:

- The cosign claims were validated

- Existence of the claims in the transparency log was verified offline

- The signatures were verified against the specified public key

7bace1f81455088b6690a44e99cabb602259ddf7

Keeping in sync

Once a server is in the registry, we don’t want maintainers needing to hand‑edit pins every time they merge something into their upstream repos (they have better things to do with their time), so a new automated workflow scans upstreams nightly, bumping source.commit when there’s a newer revision, and opening an auditable PR in the registry to track the incoming upstream changes. This gives you the security benefits of pinning (immutable references to reviewed code) without the maintenance toil. Updates still flow through pull requests, so you get a review gate and approval trail showing exactly what new code is entering your supply chain. The update workflow operates on a per-server basis, with each server update getting its own branch and pull request.

This raises the question, though: how do we know that the incoming changes are safe?

AI in the review loop, humans in charge

Every proposed commit pin bump (and any new local server) will now be subject to an agentic AI security review of the incoming upstream changes. The reviewers (Claude Code and OpenAI Codex) analyze MCP server behavior, flagging risky or malicious code, adding structured reports to the PR, and offering standardized labels such as security-risk:high or security-blocked. Humans remain in the loop for final judgment, but the agents are relentless and scalable.

The challenge: untrusted code means untrusted agents

When you run AI agents in CI to analyze untrusted code, you face a fundamental problem: the agents themselves become attack vectors. They’re susceptible to prompt injection through carefully crafted code comments, file names, or repository structure. A malicious PR could attempt to manipulate the reviewing agent into approving dangerous changes, exfiltrating secrets, or modifying the review process itself.

We can’t trust the code under review, but we also can’t fully trust the agents reviewing it.

Isolated agents

Our Compose-based security reviewer architecture addresses this trust problem by treating the AI agents as untrusted components. The agents run inside heavily isolated Docker containers with tightly controlled inputs and outputs:

- The code being audited is mounted read-only — The agent can analyze code but never modify it. Moreover, the code it audits is just a temporary copy of the upstream repository, but the read-only access means that the agent can’t do something like modify a script that might be accidentally executed outside the container.

- The agent can only write to an isolated output directory — Once the output is written, the CLI wrapper for the agent only extracts specific files (a Markdown report and a text file of labels, both with fixed names), meaning any malicious scripts or files that might be written to that directory are deleted.

- The agent lacks direct Internet access — the reviewer container cannot reach external services.

- CI secrets and API credentials never enter the reviewer container — Instead, a lightweight reverse proxy on a separate Docker network accepts requests from the reviewer, injects inference provider API keys on outbound requests, and shields those keys from the containerized code under review.

All of this is encapsulated in a Docker Compose stack and wrapped by a convenient CLI that allows running the agent both locally and in CI.

Most importantly, this architecture ensures that even if a malicious PR successfully manipulates the agent through prompt injection, the damage is contained: the agent cannot access secrets, cannot modify code, and cannot communicate with external attackers.

CI integration and GitHub Checks

The review workflow is automatically triggered when a PR is opened or updated. We still maintain some control over these workflows for external PRs, requiring manual triggering to prevent malicious PRs from exhausting inference API credits. These reviews surface directly as GitHub Status Checks, with each server being reviewed receiving dedicated status checks for any analyses performed.

The resulting check status maps to the associated risk level determined by the agent: critical findings result in a failed check that blocks merging, high and medium findings produce neutral warnings, while low and info findings pass. We’re still tuning these criteria (since we’ve asked the agents to be extra pedantic) and currently reviewing the reports manually, but eventually we’ll have the heuristics tuned to a point where we can auto-approve and merge most updated PRs. In the meantime, these reports serve as a scalable “canary in the coal mine”, alerting Docker MCP Registry maintainers to incoming upstream risks — both malicious and accidental.

It’s worth noting that the agent code in the MCP Registry repository is just an example (but a functional one available under an MIT License). The actual security review agent that we run lives in a private repository with additional isolation, but it follows the same architecture.

Reports and risk labels

Here’s an example of a report our automated reviewers produced:

# Security Review Report

## Scope Summary

- **Review Mode:** Differential

- **Repository:** /workspace/input/repository (stripe)

- **Head Commit:** 4eb0089a690cb60c7a30c159bd879ce5c04dd2b8

- **Base Commit:** f495421c400748b65a05751806cb20293c764233

- **Commit Range:** f495421c400748b65a05751806cb20293c764233...4eb0089a690cb60c7a30c159bd879ce5c04dd2b8

- **Overall Risk Level:** MEDIUM

## Executive Summary

This differential review covers 23 commits introducing significant changes to the Stripe Agent Toolkit repository, including: folder restructuring (moving tools to a tools/ directory), removal of evaluation code, addition of new LLM metering and provider packages, security dependency updates, and GitHub Actions workflow permission hardening.

...

The reviewers can produce both differential analyses (looking at the changes brought in by a specific set of upstream commits) as well as full analyses (looking at entire codebases). We intend to run both differential for PRs and full analyses regularly.

Why behavioral analysis matters

Traditional scanners remain essential, but they tend to focus on things like dependencies with CVEs, syntactical errors (such as a missing break in a switch statement), or memory safety issues (such as dereferencing an uninitialized pointer) — MCP requires us to also examine code’s behavior. Consider the recent malicious postmark-mcp package impersonation: a one‑line backdoor quietly BCC’d outgoing emails to an attacker. Events like this reinforce why our registry couples provenance with behavior‑aware reviews before updates ship.

Real-world results

In our scans so far, we’ve already found several real-world issues in upstream projects (stay tuned for a follow-up blog post), both in MCP servers and with a similar agent in our Docker Hardened Images pipeline. We’re happy to say that we haven’t run across anything malicious so far, just logic errors with security implications, but the granularity and subtlety of issues that these agents can identify is impressive.

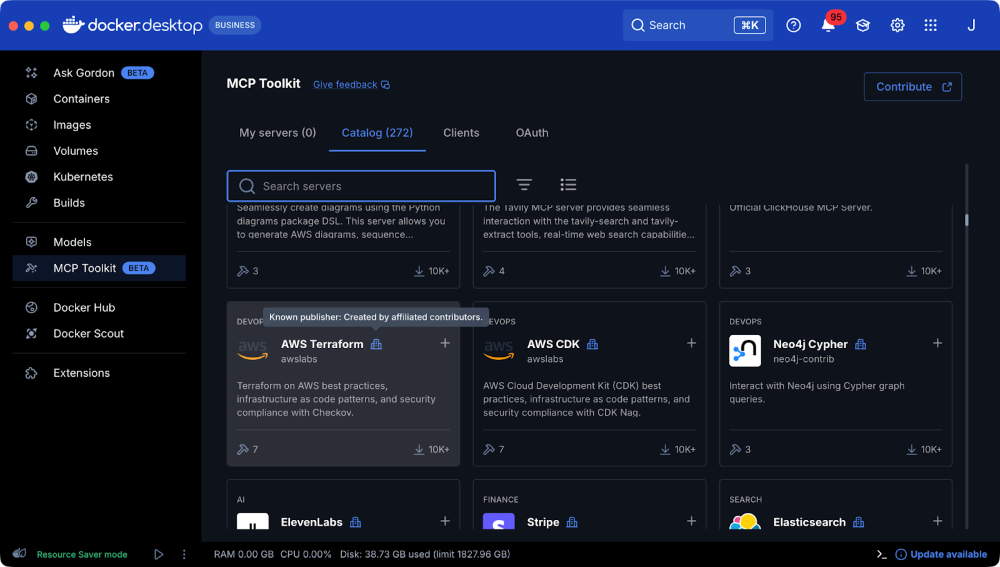

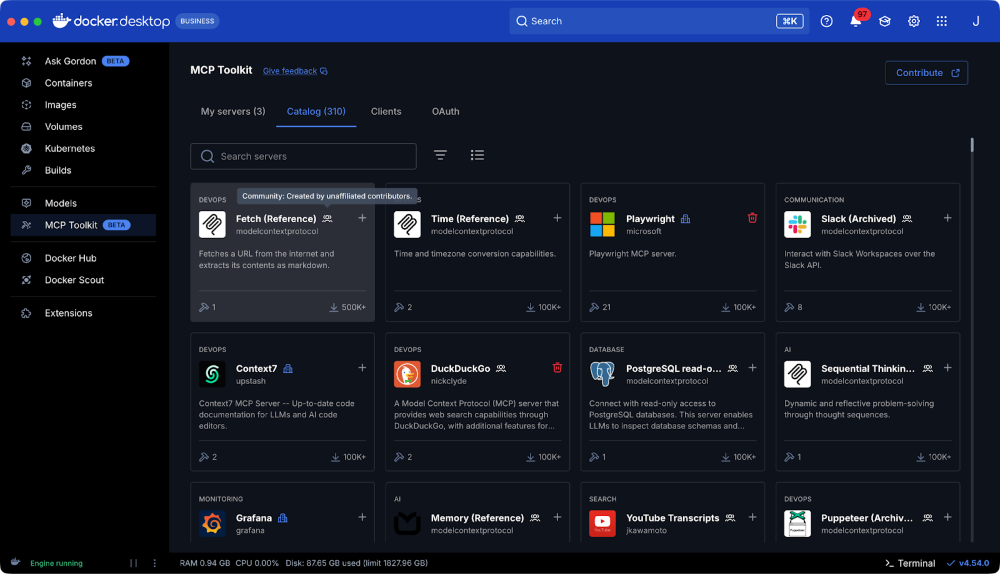

Trust levels in the Docker MCP Catalog

In addition to the aforementioned technical changes, we’ve also introduced publisher trust levels in the Docker MCP Catalog, exposing them in both the Docker MCP Toolkit in Docker Desktop and on Docker MCP Hub. Each server will now have an associated icon indicating whether the server is from a “known publisher” or maintained by the community. In both cases, we’ll still subject the code to review, but these indicators should provide additional context on the origin of the MCP server.

Figure 1: Here’s an example of an MCP server, the AWS Terraform MCP published by a known, trusted publisher

Figure 2: The Fetch MCP server, an example of an MCP community server

What does this mean for the community?

Publishers now benefit from a steady stream of upstream improvements, backed by a documented, auditable trail of code changes. Commit pins make each release precisely attributable, while the nightly updater keeps the catalog current with no extra effort from publishers or maintainers. AI-powered reviewers scale our vigilance, freeing up human reviewers to focus on the edge cases that matter most.

At the same time, developers using MCP servers get clarity about a server’s publisher, making it easier to distinguish between official, community, and third-party contributions. These enhancements strengthen trust and security for everyone contributing to or relying on MCP servers in the Docker ecosystem.

Submit your MCP servers to Docker by following the submission guidance here!

Learn more

- Explore the MCP Catalog: Discover containerized, security-hardened MCP servers.

- Get started with the MCP Toolkit: Run MCP servers easily and securely.

- Find documentation for Docker MCP Catalog and Toolkit.